AIA Wyoming recently sat down with architect Tim Belton from the firm Malone, Belton and Able. Getting to know a bit about him was informative and insightful, and we appreciate him sharing a brief part of himself with us.

How did your childhood experiences as the son of a Foreign Service officer influence your development as an architect?

I’ve lived in some truly amazing houses as I was growing up, but besides the homes, I was exposed to architectural masterpieces around the globe. I have always had great respect for architecture and the architects who create it.

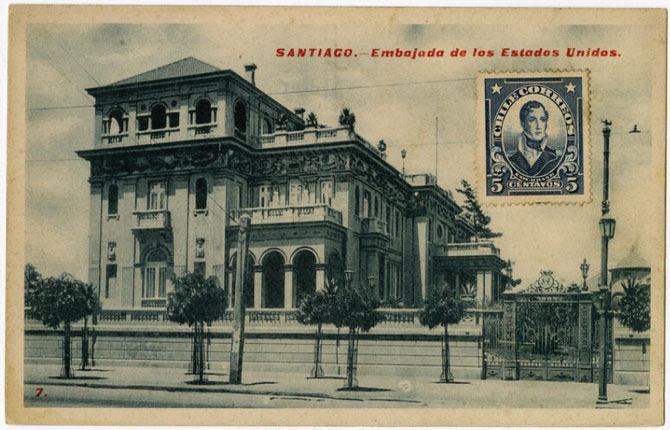

I remember a lot of the spaces and details in the places I lived. There’s an example of that in Santiago, Chile, where I lived between ages six and eight. When we got there in 1956, our family was told to use the embassy residence until the ambassador showed up. We found ourselves in the Palacio Bruna, built circa 1918 and designed by Chilean architect Julio Bertrand. It was of Italian Renaissance style, highly ornate and very imposing.

We only lived there for three or four months, but I remember it quite well. I last lived there in 1957. The place was enormously fancy with 17 bedrooms with en suite bath. There was a servant’s stairway and a dumbwaiter with an opening on the third floor. The people who ran the house saw me as an interloper and didn’t allow me into the kitchen, so I would ride down the dumbwaiter from the third floor and sneak in for snacks.

I went back to Santiago for an international AIA convention in 1996 with a few other U.S. architects and decided to visit this place I’d lived, but the U.S. government had sold the building to the Chilean Chamber of Commerce the year before. When we were there, it was 3.5 floors, but the Chamber had added to it, so it was now a full four stories, with an added guardhouse.

When I presented myself at the guardhouse, the guard knew nothing about it having been the American Embassy and certainly thought I was lying about having lived there, but he let me talk to one of their tour guides. The guide was suspicious of me, too, so I told him about the servant’s stairway, and we went to the third floor where the dumbwaiter opening had been turned into a closet. I asked him to take out the stacks of paper and office supplies inside, and said he would find two rails on the back wall for the dumbwaiter. And there they were. When he saw them, he believed my story, welcoming me back. He showed me all the rooms, including the dining room with a table for 22; and one that had been my bedroom, now an office. The guide introduced me to people as we wandered through, letting me take photos.

That sort of stuff influenced me from a very young age.

What are your favorite places and cultures in the world?

Chile was one of them. Others include Rio de Janeiro; Paris; Venice and the island of Sicily; Marrakesh; Athens and the island of Crete; Vancouver B.C.; Washington D.C.; San Francisco; Chiang Mai in Thailand; Kyoto, Japan; then circling back to South America, Cuenca in Ecuador. These are favorite places and favorite cultures. They were all fabulous then; some much changed now.

When and why did you decide to be an architect?

I was about 12 years old, living in Canberra, Australia, where I enjoyed making mechanical inventions and building models of ships from kits. The inventions were just my own weird things, robots and such. My dad told me building models was related to architecture, and he said I might want to think about becoming an architect. I did think about it; not seriously though, just a seed planted.

Tell us about your university education at Stanford and the University of Oregon. What is urban anthropology? What was the most important thing you learned at Stanford, in Oregon or both places?

Urban anthropology is a subset of cultural anthropology. It’s the study of cultural systems in cities and towns and how people relate to the built environment. It also involves studying the social and economic forces that shape how cities, towns and neighborhoods develop.

In architecture, urban anthropology has been important to me because I want to incorporate the elements that will make a place special to the people who will be using it. To do that, I need to understand the clients’ specific cultures. Whether designing a home, an office, a public facility or doing a master plan, an understanding of urban anthropology can make a building more responsive to people. That’s why I went into urban anthropology before architecture school.

Urban anthropology did influence my professional work. For example, we did an office building in Sheridan where we were to give every office an excellent view of the Big Horns. That meant we had long hallways, and to ensure the people along them were not isolated, we created three offshoot hallways with meeting points and mini coffee bars at the intersections where people could sit and talk. The meeting points were an essential part of how people interacted in their office environment. We made it easy to pass someone in the hallway, say hi, grab a coffee and sit down. Informally discussing ideas and projects improved their work, but those interactions wouldn’t have happened without the meeting points. That’s urban anthropology at building scale.

The variety Stanford offered me was incredible. I studied a small hilltop village in Tuscany. I took classes in art history and principles of design that were pure aesthetics not related to buildings. Later I spent a summer researching the creation of Brasilia, the unfortunate new capital of Brazil.

In Oregon, I could concentrate on pure architecture and related fields for 3½ years. That allowed me to hone my skills as a designer. My professors taught me to balance art and logic. Buildings are complex, and you don’t want to have one that accomplishes just one thing. It needs to accomplish many things. You want to surprise your client with what it can accomplish and make a rich environment for whatever people do there.

Tell us about Malone Belton Abel, which was founded in 1961 by Adrian Malone. Did you join the company in 1984, when you began managing it, or did you arrive earlier? Why the focus on environmentally sensitive design?

Adrian Malone was a really fine architect and an amazing gentleman. After spending most of his career in San Francisco, he left in the 1950s because San Francisco was already “too crowded.” He spent a few years around Jackson Hole, and then he came to Sheridan and Big Horn for good in 1961.

I stopped by to interview for a job in 1976, and Adrian hired me as a young apprentice architect. The firm exuded class because of him. The company’s atmosphere wasn’t pushy at all; it had an understated elegance that came from who he was as a person and as an architect. I could feel it even though, at first, I could not quite put my finger on it. I went around to the other offices in town before I was hired, but there was no comparison. The atmosphere was an important part of the firm and was a big part of what I learned from Adrian. He eventually asked me whether I wanted to become a partner and run the place, and I told him I would be happy to, and I bought him out a few years later when he decided to sell.

In a small town, you have to develop what you can with a small group of really good people and do everything you can to make them happy, which means pretty much leaving them alone to do their work. We had 10 to 15 people, and it was just a very comfortable and stable place where the core people stayed for 20 to 25 years. Architecture schools don’t teach office management or the business side of things, but managing our firm was simple: respect the people you work with; recognize that they know what they’re doing; support them in their work.

Environmentally sensitive architecture wasn’t a big thrust when I was starting out, but it has always made sense to me. In 1979 Adrian and some doctors got together to build a small office building for their businesses, and I suggested putting solar panels on the roof to take advantage of the south orientation. Nobody objected. These air-circulation-based panels functioned really well for about 30 years before the fans stopped working. We’re still in that building and replaced the panels with a photovoltaic system in 2019.

Malone Belton Abel offers services in architecture, master planning, structural engineering and interior design. It seems to focus on public buildings, with 40% of your projects identified as educational and only 6% as residential. Did you specialize within the company? What is your favorite kind of project?

In addition to management, which wasn’t that intense, I was involved in the design of all our projects. We had a very collaborative office, so I shared that responsibility with other architects in the firm. Our designs were the product of many good minds.

My favorite design type has been for the arts, whether visual or performing: museums, visitor centers, theaters, and art production places. I knew a lot about what museums needed long before designing my first one because I’ve paid attention while visiting scores of museums in far-flung places.

Of what career accomplishment are you most proud?

There are several. The first is the aggregate of more than fifty projects I did at the University of Wyoming in the three decades from 1989 to 2019. Some were small, complex renovations to historic buildings, others were major new facilities such as the Berry Biodiversity Conservation Center. One, the Visual Arts Facility, was honored with a COTE award in 2016.

The second is the total renovation, including a new façade, of the historic WYO Theater in Sheridan. I had a great client with great ideas, Lynn Simpson, and was able to let my creativity loose on what was basically a blank canvas.

The third is the N.E. Wyoming Visitors Center near where I-90 enters Wyoming from South Dakota. This center is the first, and I think only, Net Zero Energy building owned by the state. It features every energy-saving architectural trick in the book; a large array of ground-source heat pump wells; and 50KW of PV panels integrated into the roof design. Because of Wyoming’s freakish political climate, we weren’t allowed to use any wind turbines, but the PV panels turned out to be enough.

My unquestionable favorite is the Forrest E. Mars, Jr., building at the Brinton Museum near Big Horn, Wyoming. It continues to be very well received and is a source of great pleasure to me.

Forest Mars was the eldest of three children who owned the Mars candy company as a family. They wanted the museum to be a world-class facility, but that was about all they specified. The museum director had a few more requirements: a minimum of windows to prevent ultraviolet light from coming in through the glass and ruining delicate artwork; and the whole place to be built into the hillside to have the least visual impact on the surrounding Big Horn foothills and historic Brinton Ranch House.

The museum has a rammed-earth wall coursing through it that is the heart of the building. We did add a bit of Portland Cement and some reinforcing bar, but it really is mainly dirt, gravel and sand. The wall is 250 feet long and 56 feet high, and it’s not likely to be going anywhere soon. When I asked Mr. Mars for approval for the extra $2 million it would cost to build, he asked if a mainly dirt wall would last. The answer was that large portions of the Great Wall of China are made of rammed earth — without any Portland Cement — and they’ve been in place about 2,000 years.

What are some of the challenges currently facing the profession, as opposed to when you became an architect?

The low-fee bid selection system for selecting architectural firms is a big challenge across the profession, and I would like to see architects work together to make it go away by refusing to submit actual “bids.”

The federal government and knowledgeable private individuals use the qualifications-based selection (QBS) system to select architects for jobs. The idea is to select the most qualified firm for the job … what a concept! The architect who is selected then negotiates the fee with the client. The client only goes to someone else if the two parties can’t agree on the fee. There is no downside.

Putting a building together involves a ton of work, hours, and experience managing the engineers, landscape architects, and other specialists. High-end clients want the best architect. They know they can figure out the fee, but they also know it won’t be cheap.

Unfortunately, the QBS system is sometimes replaced by a selection system based on low fees. The cheapest “bid” wins the job, but it makes sense in a way, as the people who use this system are typically not looking for quality in design.

Here’s why this matters: Better firms often won’t participate in low-fee-based selection projects and are not chosen as often if they do, which means lesser-qualified firms end up designing the built environment that influences so much of our lives. As a result, the low-fee system causes problems that hurt both the architectural profession and the general public.

How do you feel about the evolution of the architectural industry during your career as an architect?

Any architect my age would say using computers to create 3-D imaging and designs has been the big evolutionary step.

When I started, architects had to communicate their designs by using two-dimensional drawings and by building small-scale models. That changed in the early 1990s, and now everything is done in 3-D.

What criteria would you apply to decide whether a building is “good”?

A building has to do many things at once to be good, but we want it to be more than good. We want it to be excellent. Here’s my list:

- Fundamentally, it has to function very well for its intended uses.

- The amount of energy used by buildings is enormous, so we have to do everything we can to design a net-zero energy building that is environmentally responsible.

- It has to be aesthetically pleasing, whatever that means to the architect and the client. That part will vary all over the map.

- Occupants have to feel exhilarated to be in and around it. If you ask someone what they think of the building, you don’t want them to say, “It’s fine.” You want them to say, “I love it.”

What do you think is the best building in Wyoming?

Although I haven’t seen every building in the state, Yellowstone Park’s Old Faithful Inn has to be one of the best. The lobby is crazy fun, and if you get a room in one of the old wings, you just have to love it.

What would your advice for a young architect be?

Take English literature and writing classes. They aren’t required as part of any architect’s training because the people who put together the curricula don’t understand their importance after graduation. As a result, the number of architects who can’t put together a coherent, well-written letter or proposal is legion.

Any last thoughts?

Care about the greater community and get vaccinated.