The following excerpt is from a homeowner’s unsolicited 1993 letter after receiving drawings of their house that were designed by Eugene “Jeep” Dehnert in the early 1950s in Billings, Montana. As per the practice of architecture, the letter’s author continued:

“… we marveled at the level of detail and foresight shown. Imagine insulated walls and combustion air for the fireplace in a time of energy glut. We do, however, have a question. What was the exhaust fan in the dining room for? We speculate there was a cigar smoker in the family.

“The initial joy in the creative process has become such a muddled, compromised product that it is difficult to consider the profession as leaders of anything. Hopefully, there are those who will continue to push the edges and create a built environment of enduring beauty for all to enjoy.”

It’s certain that although the letter was intended as a compliment, its brusque critique of the current state of the “profession” would be challenged by Jeep whenever the opportunity arrived at his drawing table during an abundant career spanning 61 years.

Born in Lewistown, Montana, his parents, Gus and Amy, moved him and his sister, Fran, to Hardin, Montana, which lies on the boundary of the Crow (Apsaalooke) Reservation. While his mother was a school teacher, Jeep was inspired towards architecture by his father, who worked at a lumber store and was also a skilled carpenter and woodworker.

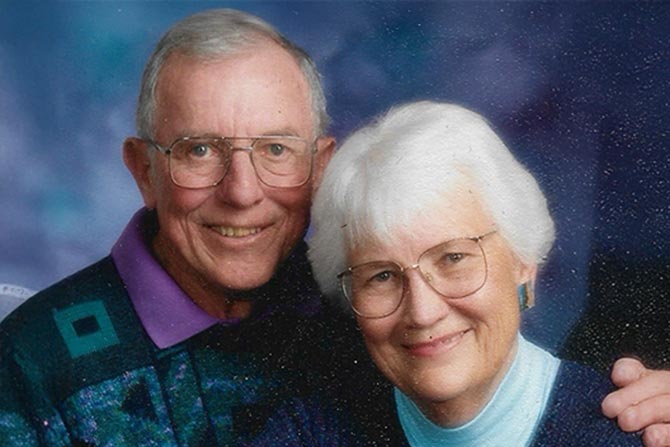

As a youngster, Jeep became passionate about music and played drums for jazz and marching bands throughout high school, college and with the United States Army Band. In one favorite story from high school, Jeep showed up ready to play with the band at the football game and ended up being a last-minute recruit to play on the football team (Hardin and other small, rural towns fielded six players). He played “somewhere” on both defensive and offensive lines for the Hardin Bulldogs until the final buzzer. The Bulldogs lost. When asked how he remembered feeling, Jeep always answered, “Pretty much slaughtered, so I stuck to the drums.” This past October, no one in Jeep’s family had the heart to tell him that his Bulldogs went 0-9 for the season. This included a failed Friday night’s squeaker against the Sidney Eagles, his beloved wife of 73 years, Charlotte Haugen’s high school alma mater.

After graduating with a B.S. in architectural engineering from Montana State College in 1951, with the onset of the Korean War, Jeep was recalled to the U.S. Army at Fort Ord in California and, soon afterward, deployed to Tokyo, Japan. There, he began his career in the Army’s Design Division of the Corps of Engineers. Attached to the United Nations headquarters, he became a member of the Far East Society of Architects. Both he and Charlotte were riveted by the Japanese people and their culture and thus began an enchantment that would endure the rest of their lives. As part of this sustained bond, the couple returned to Japan numerous times and hosted foreign exchange students. Japanese aesthetics were never too far from Jeep’s own sensibilities in design.

Following Jeep’s discharge from the Army in 1953, he and Charlotte moved to Billings, Montana, where he apprenticed under the influential tutelage of architects Nordquist and Sundell, two disciples of Frank Lloyd Wright. During his tenure with their firm, Jeep earned his NCARB and Montana licenses and gained membership in the AIA. Dehnert credited Nordquist and Sundell with providing him the conceptual tools and professional acumen with which to develop his own “voice” and practice. An inkling of that voice was sparked by the firm’s interest in modernist design aesthetics, utilizing new approaches to construction (modular concrete) and incorporating new developments in materials.

In 1960, Cornell-educated architect Bob Corbett placed an ad for a draftsman to join his “firm of one” in Wyoming. Although Jeep’s passion was design, he was anxious to get his independent career going. On a hunch, he answered Corbett’s ad. During a hastily arranged interview in Worland, Wyoming, the two architects agreed that Jeep would concentrate on working drawings for one year, and if, at the end of that year, the two still tolerated one another, they would form a partnership.

Six months into the agreement, Corbett/Dehnert Associates was established, and they moved their nascent practice to an office in Lander, Wyoming. One of the firm’s first commissions was Lander’s Northside Grade School. Their design was an innovative riff on corrugated steel ranch buildings dotting the West. The school’s classroom wings, like spokes on a wheel, jutted outward from a large, tubular sunken gymnasium that also served as an assembly hall. Its expansive ceiling was treated with a soft yellow, quilt-like spray insulation, providing an interesting contrast with the building’s industrial exterior.

During the mid-1960s, the firm was commissioned for a growing number of projects, Jeep became president of the Wyoming State Chapter of the AIA and served as a member of the NCARB committee for preparation of the National Exam. In 1965, Corbett/Dehnert Associates was hired by Bay Area Radio Executive Paul McCollister to create the Master Plan and to design numerous base buildings for the world-renowned Jackson Hole Ski Area. Because of the scale of the project, Corbett would open a second office in Jackson, and Jeep ran the one in Lander. A short time later, they provided design for the first buildings at Targhee Ski Area outside Driggs, Idaho.

Designing the large complex of the Washakie Center and three high-rise student dormitories for the University of Wyoming (UW) kick-started the firm’s long relationship with the university and its central architect, JT Banner. Because of Laramie’s inclement climate, this extensive project, dedicated in 1967, features underground tunnels connecting the dormitories with the food hall and activity spaces. The Washakie Center featured an encapsulation of the clean lines espoused by the converts of the Bauhaus yet alluded to the area’s geologic surroundings. This included a cantilever outward from its limestone foundation.

Jeep was also instrumental in design phases for the school’s uber-modern War Memorial Stadium (site of concerts by some of the world’s top bands, like Pearl Jam), the Fine Arts and Law buildings, and the infamous “Dome of Doom” Arena-Auditorium where UW has hosted major sporting events and a consequential speech by then-presidential candidate Barack Obama. The arena brought into play Jeep’s interest in the earth shelter movement but on a large scale. The floor inside was the firm’s first foray into suspended surfaces. Being a musician, he insisted that outstanding acoustics guide every design consideration, whether it was a cavernous concert hall, expansive lobby area or intimate classroom. Excellent sound was of critical importance driving many of his design features.

Following the dissolution of his partnership with Corbett, Jeep partnered with Ken Richardson, Walt Bensman and Mike Quinn. Of note, during the 1980s, Kurt Dubbe, now a noted Jackson architect, joined the firm for three years. That diverse group of architects was responsible for a growing list of clients and projects. During those years, Jeep and Charlotte also continued their friendship and professional relationship with Francie Corbett, who, in 1976, took the reins of the interior design company Contract Design. Along with the Dehnerts’ support, Francie built one of Wyoming’s most important interior design shops. Her aesthetics fit with Jeep and Charlotte’s, so there was a great deal of collaboration whenever the opportunity arose.

The Crystal Springs Hotel in Teton Village was one such project. Located next to the Base Station of the Jackson Hole tram, the hotel offered a ski equipment shop, restaurant and ensuite rooms that provided immediate access to the lower slopes. Crystal Springs’ design was a blend of European alpine and a kind of svelte Western roughrider. The Dehnerts and Corbetts sold the property in the 1980s.

The office of Dehnert/Richardson/Bensman/Quinn (DRBQ) was responsible for projects that continued to realize Dehnert’s long advocacy for sustainability. While the Corbett/Dehnert office had years before launched this vision in the design of the Jackson Hole Visitors Center, DRBQ pushed the ideology further into the “mainstream.” The Visitors Center, located on the boundary of the National Elk Refuge, featured a softly angled sod roof inspired by the West’s early Scandinavian settlers.

But it was Jeep’s design for Douglas High School in Converse County that was remarkable for its courageous delving into sustainable design, even by today’s standards. The modular concrete building was the first high school in the nation to be powered by an extensive solar array. The school’s exterior design presented angles appropriate to efficient solar collection and, at the same time, reflected the school’s location nestled amongst windswept rock outcroppings. The school district’s electric costs immediately proved the technology right for Wyoming’s climate and abundant sunlight. Additionally, the firm’s new office building in Lander was designed with one full side wall being a large solar array.

Jeep’s approach also incorporated, for the first time in school design in Wyoming, aspects of bermed earth that contributed to gains in insulation and drainage. During this period, Jeep and his team received design awards from the American Association of School Administrators for the Douglas High School, Middle School and East Elementary School. The firm’s West and North Elementary Schools in Lander also received commendations. It’s notable that the West Elementary School is a modern ideal of earth berming and has proven Jeep’s strong belief in the importance and relevance of thoughtful environmental design. Wyoming’s rest stops along the state’s major highways are great examples of his influence on design. Roof lines reflecting nearby landscapes, bermed exteriors, local materials, and passive and active solar at the rest stops are nowadays a common vernacular as one travels the state.

Jeep maintained an avid interest in Italian-American architect Paulo Soleri, who was hugely innovative (albeit brutalist) in sustainability and communal living, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s astute adherence to allowing materials to speak for themselves in refined ways. An Episcopalian all his life, Dehnert’s Trinity Episcopal Church, situated on the banks of the Popo Agie River in Lander, is a striking example of his melding of both Soleri’s and Wright’s architectural “theologies.” Employing heavy flying buttresses of conglomerate concrete, the building is diamond shaped and puts to use beautiful stained-glass windows repurposed from the original church once located near Lander’s Main Street. Jeep and Charlotte’s friend, Casper/Santa Fe sculptor Gene Tobey, created the church’s large, vigorously carved wooden cross that hangs suspended over the altar.

While the firm’s reputation and economy were built on large-scale projects, Jeep was passionate about designing homes for private clients. His and Charlotte’s homes in Billings and Lander offered the opportunity to play with materials, explore structural flourishes and display a personal brand of aesthetics gathered from voracious research, travels and influences. Both houses enjoy extraordinary views through banks of windows, sunken living rooms, heavy beams that span open spaces and unique outdoor entryways that embrace the natural surroundings while welcoming visitors to a unique design experience. The acclaimed Johnson House, designed to meander amongst red limestone cliffs near Sinks Canyon, offers a dynamic roofline that provides enough verticality for an impressive wall of windows looking out towards the valley below. Its reliance on natural materials and shape allows the dwelling to merge with the arid landscape.

Perhaps Jeep’s favorite was the residence he designed for his and Charlotte’s pottery teacher, Mary MacDonald. The exquisite house is situated in the back of a tiny lot in Cedar City, Utah, and puts to use his talent for making special those limitations that he and the client were challenged by. The MacDonald house is, in a way, a master study in the sensitive use of local materials, lines that create a sense of space greater than that which exists and a sophisticated interior flow.

Once, when asked to describe the foundation of his design philosophy, Dehnert stated that he tried to “focus on strategies inspired and informed by the nature of architecture and the architecture of nature.” Pretty simple stuff, indeed.

Dehnert, 97, died peacefully in his sleep on Oct. 12, 2024, in the house that he and his beloved wife, Charlotte — with a young family in tow — built in Lander, Wyoming, in 1965. Charlotte was a journalist and predeceased Jeep in October 2023.