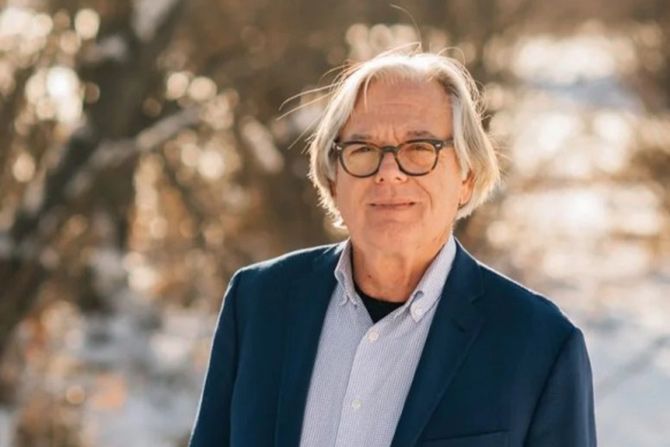

Tom Ward’s path to architecture began long before he ever set foot in a design studio. Raised in a blue-collar family that hopscotched across the American heartland before settling in Wyoming, he grew up surrounded by builders, makers and problem-solvers. Those early influences followed him through a decade in New York City and eventually back to Jackson Hole, where he co-founded Ward+Blake Architects in 1996. By the early 2000s, Ward was not just designing buildings — he was inventing new ways to create them, developing a patented post-tensioned rammed-earth system known as “Earthwall,” an early marker of his commitment to low-carbon construction.

Ward credits his architectural education at Arizona State University with sharpening that instinct. Immersed in one of the nation’s leading programs for passive and active solar design, he began to understand how architecture could be both expressive and deeply responsible — how materials, climate and energy could shape a building as much as aesthetics. That foundation would become a throughline in his work.

Designing with an eye toward land stewardship came naturally to him. Over the decades, his practice evolved to embrace a vision of environmentally specific architecture — work that responds not just to people, but to place. For Ward, sustainability isn’t a trend; it’s an ethic, one born from growing up surrounded by tradespeople and wide-open Wyoming landscapes and later reinforced by curiosity and experience.

In conversation, Ward is reflective, candid and often funny — equally ready with a philosophical aside or a story from a job site. When we sat down with him, he spoke about the unexpected path that led him to architecture, the mentors who shaped his imagination, the projects that pushed his practice forward and the challenges facing today’s designers. What follows are excerpts from that wide-ranging discussion.

When and why did you decide to become an architect?

I come from a family of blue-collar building titans. My dad was in the oil business. He was what they called a “tool pusher,” selling oil field drilling equipment. But that wasn’t his background; he was educated in geology and economics and worked in the oil field to support his family. Because of that, we moved a lot — from Michigan down to Abilene, Texas, and all the way across the breadbasket of America. We finally ended up in Casper, Wyoming, which is where I spent all my formative years. I had an idyllic childhood and consider myself a Wyoming native.

My grandfather was in the trades. He was a pipe fitter. But he was also a jack of all trades. He was so good with his hands that there was nothing he couldn’t do. He was the mayor of Wapakoneta, Ohio, for six terms, and he played first and second violin in the orchestra. I used to go back east for about six weeks in the summer and spend time with him, which was a lot of fun. Those summers with him really left a lasting impression.

He was old-school; he still wore a black vest, a white shirt and a tie with heavy trousers to crawl under houses and do plumbing. He would take me on job sites and show me how to do whatever he happened to be doing at any given time. When I was 7 or 8, he took me aside and said, “Tommy, if you become a tradesman like me, I’m going to be very disappointed in you.” That’s kind of heavy for an 8-year-old. When I asked why, he said, “You should be telling people like me what you need done, not doing it yourself.”

As I got older, I became more interested in trades. I’m an absolute gearhead when it comes to cars, especially European cars, and for a while, my dream was to build hot rods. But no one was doing that in Casper, Wyoming; there was no outlet for that. In high school, I got interested in cooking and decided I was going to be a chef. I got a job at one of the better restaurants in town, and I worked my way up. But after spending more time in commercial kitchens, I knew I didn’t want to be doing that.

Then my dilemma became: What do I do? I liked to build cars, and I liked the creative aspect of cooking and assembling ingredients. Then, at a career day in 9th grade, there was an architect there. He was showing a rendering of a building, and it all came together like nuclear fusion. It dawned on me: yeah, there are people who design buildings, and that’s how they get built.

There were some really, really interesting buildings in Casper, Wyoming, in the ‘60s and early ‘70s, and after that career day, I started noticing them. There’s a bank in downtown Casper that’s still there; it’s all concrete shell structure and looks like a segmented orange. I remember walking by it as a kid and noticing the curved glass and curtains that somehow followed the contour of the building. It lit me up, and I never looked back after that. I knew that was what I wanted to do.

Did any architect, in particular, inspire you?

Carlos Scarpa. He did something that no architect I’m aware of has been able to do, which was to fuse ancient techniques of forging and metalwork into a modern vocabulary. I was lucky enough to see his work in print in New York, but then I went to Verona, Italy and was able to see a lot of his work there in person.

One example of his work was a renovation of a medieval barracks, which was turned into a small museum. Wherever his work stopped and the existing structure started, or vice versa, he celebrated that edge with a flourish. You’d have this brick building with walls that were two feet thick, and then he’d put in a piece of bronze and start a hand-thrown plaster partition. He was able to forge, literally, iron railings for that job and insert bronze pieces into them. Where they touched, he made a keyhole, and they fit together.

When I was in Venice, I knew he’d worked on that museum and built a bridge across one of the canals to get to it. We wandered around a tiny plaza for hours, looking for the museum, until I saw something sticking out behind a church’s nave that could only be his work. And sure enough, it was his bridge into this building.

The building was designed so that when tidal surges come, the lower floor floods. He allowed it to flood, and it became a water feature in the building. When the waters recede, it’s the lobby of this museum. I was thrilled when we finally saw it.

Carlos grew up and lived in Venice. I think, as an architect in Italy, your role is challenging, because you’re surrounded by stuff that’s classical and ancient. But he found a niche, and he made it more compelling intellectually by putting his work in that context. I have never seen anything that left me slack-jawed like that. It was really something to see.

What career accomplishment are you proudest of?

I hope I haven’t done it yet. That’s my answer. But there is one project that was kind of a breakthrough for us: the Warsaw residence in Jackson Hole. The client was interested in something not typical for Jackson Hole, and they owned a lot in a really restrictive CC&R environment, if you will.

They wanted me to explore the possibilities, so we designed a building that was decidedly modern, but also could have been built 200 years ago. I learned a great deal when I presented it to the Architectural Review Board. They were steely-eyed, and as soon as I showed them the first drawing, I knew they were going to say no.

But there was one influential member of the board, Mike Hammer, who became my patron saint of architecture in Jackson Hole. The rest of the review board hated everything about the house; they hated the concrete, the inverted butterfly roof, everything. But after the brouhaha died down, Mike spoke up and said to the board, “I understand all your comments, but the local architecture here should respond to the natural environment.” He pointed out how the design was oriented to get south light and pull it clear into the house, and to maximize the view of the Tetons on the north side.

He said, “This house responds to the natural resources on this lot in spades, and I think we should approve it on that alone.” And because of that, the rest of the board agreed and approved it. So that particular house was kind of groundbreaking, and it’s one that I’m particularly proud of because we took a big chance.

What is the most important lesson you learned over your career? Is there anything you would have done differently?

I would shut the hell up and listen more. When I have managed to curb my enthusiasm a bit and listen, I have always gained some neat insights. But when you’re busy talking, trying to market yourself, you don’t always hear that. Shutting up is a big deal because then you can start hearing people’s stories. And if you’re thoughtful about it, you can formulate questions that are relevant to their life experiences and have a dialogue that makes for a meaningful and mutually fulfilling project.

There’s an architect marketer who doesn’t really appeal to me, but he said something interesting about the architects’ process. We architects love to talk about process, even though nobody really cares about it or understands it. But this marketer said, “You don’t want to know how to make sausage, but you want to appreciate the sizzle.” Nobody wants to learn how to stir eggs, but they want a perfect omelet. The proof is in the work and how you execute it, so focus on that.

What are some of the challenges you see currently facing the profession, as opposed to when you became an architect?

Carbon issues. I have a biochemist friend who says, “It ain’t the carbon, it’s what it took to get it.” We’re bombarded on a daily basis with greenwashing; manufacturers and marketing people will use any tactic to get us to buy their products, including portraying them as green and socially conscious — even when they aren’t.

The fact of the matter is that we live in a highly industrialized world. I’m not a tree hugger, but what we’ve done to Mother Earth is pervasive. The Snake River is considered a pristine ecological watershed because it only harbors native fish, but those fish are full of nitrates. They’re polluted right down to their living and functioning.

I think we’re all trying to get a handle on what we’re doing to the planet, but I don’t think the answer is the latest and greatest building materials — it’s being smart and using what we have responsibly. I think we need to start looking at building projects and talking about lifecycle costs, as well as how to make things durable and easy to maintain.

Building is such a gigantic commitment of time and energy. You ought to plan it carefully and build something that can last, so you don’t have to do it again anytime soon.

What advice would you give a young architect?

I would tell them to do it for passion. It’s a lousy business to be in if you’re solely interested in making money. But if you have a passion for it and it clicks, there is nothing that clicks as loudly and perfectly.

It’s a big responsibility we take on every day, so take it seriously. We once tracked the number of people who worked on one of our projects from start to finish, and it was over 300. We have to tell all those people what to do to some degree. It’s the kind of job my grandpa told me he wanted me to have when I was a kid, so I think he’d be proud.